It was a quiet Olympic Games in 2021. With spectators banished from the stands, and some competitors unable to participate due to never ending Covid pandemic, the titanic battle between the world’s greatest athletes was a more muted affair this year. Those who wanted to travel to the games to support their fellow citizens could only do so from the comforts of their own homes, and the great city of Tokyo did not get the opportunity to showcase its many charms on a global stage. While an international sporting competition may have been a good excuse to visit this thriving metropolis, the truth is any reason would be good enough to jet off to the Japan’s capital. Make sure Tokyo is at the top of your bucket list when the skies open up again.

September 2018 was a very different world from today. Coronavirus infection disease, that’s Covid to you and me, had still not been born in Wuhan (whether in a wet market or a lab), and gone on to conquer the planet. Our lexicon didn’t include the words lockdown, social distancing or PCR tests, and getting on a plane was a comparatively straightforward process, unlike today when it’s easier to get into college than it is to board a flight. I decided to head to the Land of the Rising Sun that year for my annual travels. My primary reason for going east was to visit a friend who lived on the southern Japanese island of Kyushu, but I also intended to sample the best that Japan had to offer while I was there. Having searched for cheap flights for months, I finally managed to beat the Google Flights algorithm and secured return trip tickets for the ridiculous price of €470. I had to fly with an airline called Xiamen Air, which I had never heard of before, but at €470 how bad could it be?

Having left work in Cork at 5 PM, went home to finish the arrangements, then caught a 3 AM bus to Dublin, on which I mercifully managed to sleep for the entire journey, I arrived at the airport with all my credentials. Then I got this sudden sinking feeling that I had been scammed. €470 round trip from Dublin to Tokyo with “Xiamen Air”. How could I be so stupid. I approached the check-in desk with my booking reference, and expected to be greeted with a look of incredulity by the woman working there. However, it turned out my booking was legitimate, the only problem was that the seat allocation system was locked and so it assigned seats randomly. My first flight was only a short hop from Dublin to Amsterdam, but the next one was a whopping 11 hour journey to China, and I had been allocated 86 B. That sounded like a recipe for deep vein thrombosis.

The pilot signed off the painless Amsterdam flight with the line, “Thank you for flying with KLM, and if you have a connecting flight we hope it is almost as enjoyable as this one.” I prayed that he’d be right. The layover in Amsterdam’s Schiphol Airport allowed me just enough time to disembark the first flight and hightail it through the massive terminal to the connecting gate where they were already boarding. I trepidatiously entered the plane, and when I did I found a clean, spacious, comfortable and colourful cabin, with a friendly crew welcoming us on board, and soft, soothing music (I think it was the soundtrack to “Forrest Gump”) to put us all at ease. I moved slowly down the plane to find 86 B, expecting I was about to face 11 of the most cramped hours of my life. Then I discovered 86 B was at an emergency exit, where I had enough legroom to to practice butterfly kicks without disturbing any passengers. All of a sudden the omens were looking up.

I drifted in and out of consciousness over the next few hours as we glided across the globe to China, where we landed in the small hours of the morning. Though I was viewed with considerable suspicion by a team of immigration officers, I managed to clear the process without any problems, and do likewise at emigration at the other side of the terminal, where I then boarded the next plane (not as comfortable, but the journey wasn’t as long) and floated off to Japan. Slumber washed over me like a tide, but during my waking moments I caught glimpses of exotic locations like Taiwan, the South China Seas and ultimately the Japanese archipelago. It was hardly 36 hours since I’d left work, and I was now about to land at Tokyo’s Narita airport.

Airports are exciting portals into a new world. From the moment of arrival you get a very brief taste of your new country’s culture: signs written in the native language, billboards advertising new and unusual products and services, different bathroom designs (the toilets in Japan practically sing to you) and a symphony of unfamilair words, clothes, people and sounds. Narita airport was a model of clinical and ergonomic efficiency, which gave a very favourable impression of the host country. My bags didn’t manage to complete the trip from Amsterdam, but the staff member at the airport assured me, with the customary Japanese politeness, that it would be delivered to my accommodation as soon as it arrived.

The airport is about an hour outside the city, so I finally emerged onto the streets of the Japanese capital around 5 PM on a quiet Sunday afternoon. My first experience of Tokyo was a narrow backstreet, where office blocks, apartments and small businesses lined the road. There was little traffic, few pedestrians, and not many signs of life. I would learn in the days to come that Tokyo is a city of contrasts. Much of the city consists of unhurried small streets like this one, usually wide enough for only one car, with a delineated space for pedestrians, and a tangled web of electrical wires overhead, but then turn a corner and you could find yourself on a massive thoroughfare, populated with glass skyscrapers, the teaming masses of Japanese society, and neon signs exploding in your face on all sides. Having had no more than 7 hours sleep in the last 50 I was rapidly feeling the effects of jet lag, but even so I was anxious to get out and explore this place.

Wandering around nighttime Tokyo, having been sleep deprived for two days, was like the most serene psychedelic trip you could ever take. Having booked into my hostel I went out to get something to eat. I was staying in the district of Asakusa, and as I looked for a good place to get a bite of food, I caught my first real taste of the magic of Japanese life. Bright Kanji signs, whose meaning I had no idea of, lit up the fronts of shops and businesses. Pedestrian crossings played music. Lawson, 7-11 and Family Mart convenience stores were located on every street corner and there were vending machines dispensing all kinds of sugary and caffeinated drinks everywhere. Many restaurants advertise their wares by placing plastic models of the dishes outside their premises. I found one place that looked quite promising and convenient, so I went inside and took a seat at a counter. Counter service is just as common as table service in Japan. In a country where people work from dawn to dusk, eating needs to be as streamlined as possible. Though the culinary arts in Japan reach a level of excellence rarely matched in the rest of the world, there’s no shortage of dining options for people in all price ranges, and the food is usually of the most nutritious quality. I looked at the menu, which thankfully had a lot of pictures, pressed a button in front of me and a server appeared. I pointed at an item and they took my order. I then took a pair of chopsticks from a dispenser in front of me and hoped for the best. It turned out I wasn’t quite as inept at this art as I thought I would be. Chopsticks lend themselves to more thoughtful and purposeful eating. You can’t wolf your food down when you are trying to delicately balance grains of rice between two thin sticks as easily as you can with western eating implements. I wouldn’t go hungry here, but I wasn’t likely to become fat either.

BRIGHT LIGHTS, BIG CITY

It was around noon the next day, a public holiday, when I was finally ready to wander out and get lost in the streets of this beguiling concrete jungle. The most pressing question was where should I begin? Though Tokyo is a famous city the world over, it doesn’t possess many tourist attractions that are household names to westerners. However, its attractions and neighbourhoods are every bit as enticing as those to be found in London, Paris, Rome or New York. I made the nearby Buddhist Senso-Ji Temple, about a 30 minute walk from my accommodation, my first stop. Tokyo may be one of the largest cities on the planet, but to a veteran walker such as myself it was a inviting challenge. There really is no better way to get a feel for a place than to explore it on foot.

One of the first things that strikes you about Tokyo is that it is a very modern city. It was originally a fishing village named Edo, which became a prominent city from 1603 when it became the seat of the feudal Tokugawa shogunate, who ruled Japan until imperial rule was restored under Emperor Meiji in 1868. The capital was then moved from Kyoto to Tokyo, which simply means eastern capital, and the city started to grow and grow. Levelled by the great Kanto earthquake in 1923, the city was quickly rebuilt but was again destroyed by the US bombers in 1945 during the second world war. A new city has since emerged from the ashes, and has expanded upwards and outwards. It’s now a hyper modern electric sugar fuelled rush of a town, pulsating with energy and vibrancy, yet similarly balanced with pockets of serenity and tranquility in its humble back streets and in its tranquil temples and shrines. Despite Tokyo’s size, people move about in an orderly fashion. There are no obvious displays of the rowdy behaviour you see everyday on the streets of other cities, there isn’t a speck of rubbish to be found, and there aren’t even any rubbish bins. I had been to Asia before, but what I had seen on my previous visits was the complete opposite of this. The largest continent on the planet was obviously the most diverse as well.

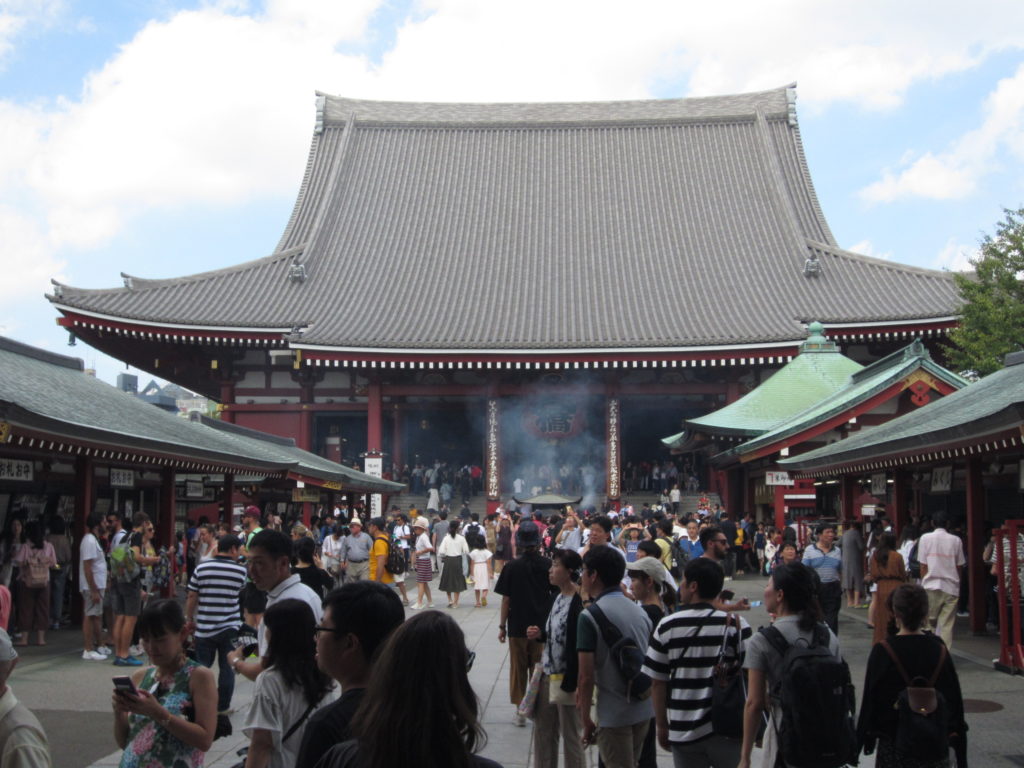

The Senso-Ji Temple is reached via a 200 meter shopping street called Nakamise. Here you can buy every type of Japanese food, cultural artefact and souvenir, and it’s not unusual to see people waltz about in traditional dress. My senses went into overdrive with the smorgasbord of sights, sounds and colours on display. At the end of Nakamise is the temple itself. Though dating back to the 7th century, the current building is a recreation from the 20th. Recreated buildings, I would discover, are the norm in Japan. Wars, fires, earthquakes and tsunamis have resulted in very few traditional buildings surviving into the modern era, but the new ones are so painstakingly crafted to look like the originals it’s hard to tell the difference.

Visiting sacred Buddhist temples require the observance of customs and codes of etiquette; people usually make a financial offering and then offer a prayer in front of the sacred object. Lighting sticks of incense and placing them in the large burners is another common ritual. Entering the temple itself, like so many places in Japan, requires visitors to remove their shoes, though as the streets are so clean one wonders what people could carry on the soles to contaminate the temple’s inner sanctum. Surrounding the temple was a sumptuously designed garden, offering a blaze of well manicured greenery bordering a well stocked koi ponds. These sights would become more and more common as my time in Japan progressed, but it was really impossible to grow tired of places which offered so much colour, beauty and serenity.

Roofed indoors streets, some of which stretch for kilometres, are ubiquitous in Japanese cities. I found a restaurant near the temple in one of Asakusa’s labyrinthine arcades, where I ate a hearty meal of seafood and noodles before I continued my exploring. I planned to make Ueno Park my next stop. Wandering across busy thoroughfares, and then along solitary back streets, I got a greater sense of life at the heart of this grand city. People lived in very compact units, they drove small cars which were tightly packed into garages stacked on top of each other. Many small mom and pop stores and restaurants lined the streets, where traditional ways of doing business survived well into the 21st century. In contrast to this were department stores and shopping malls the size of an international airport terminal. The Japanese obviously love to consume. While not much of a spender myself, I was happy to do a little window shopping when the opportunity arose. Many of these stores are 7 or 8 stories in height, with the top floors being devoted to ramen and sushi restaurants, while the basements are reserved for food stalls selling the most astonishing variety of foods. Even if you don’t purchase anything (and I didn’t) the sights and smells of these basement food paradises would be worth paying an admission price. Nothing in Japan is done by half measures. They’ve led the world in industry and technology, and their cuisine is as high tech as their white goods.

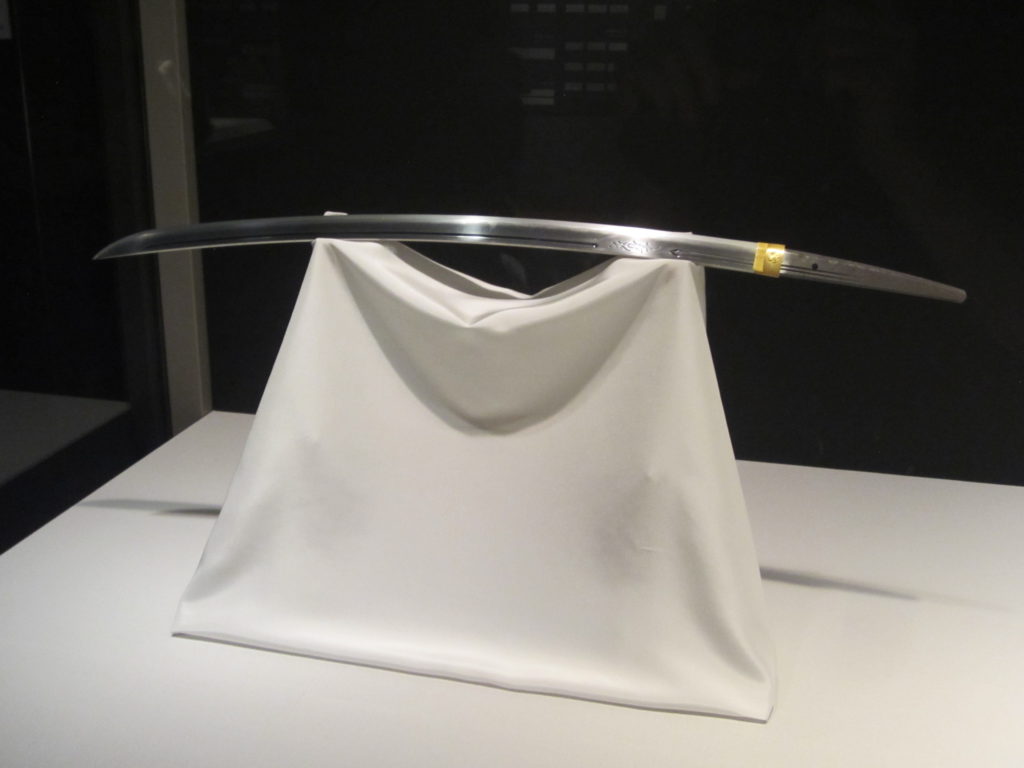

Ueno Park, one of Tokyo’s premiere green spaces, was just a short walk from the land of shopportunity. Home to several museums, a zoo, a shinto shrine, and more than 1000 cherry trees, which bloom in late March in what is must be one of the great displays of natural beauty in the world, Ueno Park is a relaxing leisure land that was part of the Kaneiji Temple during the Edo period, which lasted until 1868. I ambled slowly up its central avenue, which was sheltered by a natural canopy of branches. I went into the Tokyo National Museum, which was free due to the day being a public holiday. This establishment was rich with statues, swords, kimonos and paintings; the artefacts and treasures of Japanese history. Jet lag started to make its presence felt as I walked through this building’s cavernous exhibition spaces, but despite a few drowsy moments I managed to keep the beast at bay.

The museum closed at 6 PM, and as it did the heavens opened. I and many others waited for a while in the shelter of the foyer, hoping the rain was going to let up. But it was in for the night. After a time the proprietors of the museum opened up the gift shop to sell us all umbrellas, a very capitalist gesture, but one with an underlying sense of duty too. I wandered through Ueno Park with my new umbrella, which allowed me to fit in well with the locals. As soon as it starts to rain in Japan, all the umbrellas come out. Nobody leaves home without one. Some businesses and tourist attractions even have specially configured stands where you can lock them in place so that no one steals them. I didn’t get much of a sense that crime and theft were significant problems in the country, though perhaps people made exceptions in the case of umbrellas, necessitating this higher level of security.

Being a hippie during the summer of love in 1967 offered opportunities to take mind altering substances which opened up portals into parallel universes or states of consciousness. Walking through the neon drenched neighbourhood of Akihabara at night probably doesn’t feel all that dissimilar. Multi level stores selling all kinds of electrical gadgets brings out the inner geek in everyone passing through. This district is also famous for being the centre of Japanese okatu and anime culture, with shops brimming full of toys, cards, games, and figures. Manga cafes employ waitresses who dress in costumes, some of whom stand on the streets trying to attract business. The pervasive neon signs illuminated this entire area in a blend of surrealism and artificiality. I briefly passed through Akihabara as I made my way back to my accommodation for a night of well needed sleep, but I what I was seeing on those streets was unlikely to be very different from the content of my subsequent dreams. I had witnessed so many spectacular and unforgettable sights that day, and that was still only my first full day in Tokyo. What could the next one possibly have in store?

BRIGHTER LIGHTS, BIGGER CITY

Having managed to lop another limb off the jet lag beast with a healthy night’s sleep, I decided to head across town to the district of Shinjuku to begin my adventures on day 2. I took the subway to save time. Shinjuku station is apparently the world’s busiest, but knowing the Japanese it’s also the most efficient. It was astonishing to see how everything works so well in this country. People politely wait for trains in queuing spaces painted on the ground. There is no pushing or shoving when then doors open. Everyone files out in an orderly fashion, and then everyone else enters similarly. There is a recent true story of the high speed bullet train, known as the Shinkansen, leaving a station 20 seconds before its departure time. A national apology was issued as a result. No doubt the person responsible and their family have been in hiding ever since, owing to the shame.

Shinjuku is a modern district devoted to business, entertainment and shopping, and it has the look and feel of midtown Manhattan, only bigger, brighter and not quite as edgy. On emerging from the station I was once again enveloped in a neon infused sugar storm, and this time it was in broad daylight. A short walk from the station is the skyscraper district, home to the Metropolitan Government Office, whose observation deck on the 45th floor is open to the public, and better again is free. One really gets a sense of how enormous Tokyo really is when seeing it from a height. It literally stretched out to the horizon in every direction. This is the biggest city in the world, and there is no sense that it ever ends. On an especially clear day it can be possible to see the iconic Mount Fuji from here, but that was one sight which evaded me on this trip.

Shinjuku Gyoen, one of the city’s largest parks, was unfortunately closed the day I was in that part of town, but I walked through the wealthy streets that surrounded it as I headed south to the Meiji Dori Shrine, and then on to Shibuya. En route I stumbled across the site of the Olympic Stadium, which was rapidly being built in time for the 2020 ceremony. No one then had any idea how different the world would be by the time the games were due to open, or when they actually did. I misread Google Maps at this point and went off on a bit of a tangent from where I planned to go. Nonetheless, I never think getting lost is a waste of time, especially when you have time on your side. There’s always something new to see when you go off track, more so if you venture into a spot that doesn’t normally attract tourists. As I walked along quieter streets in more residential areas I caught glimpses of people going to and from work, friends enjoying an afternoon coffee, or people doing business in a myriad of boutiques, restaurants and galleries. Though Japan was as far from Ireland as I’d ever been, and in many ways as culturally different as any country I’d previously visited, I felt that its people and their way of life were far more similar to mine than not, and I did feel very much at home.

I remerged onto my planned path at Omote-Sando, a massive shopping street featuring all the high end branded stores, and shopping malls that are as elaborate and impressive as any museum. This district of Tokyo is a fashion lovers’ paradise. Displays of high end couture were in evidence on all sides. I, on the other hand, looked quite out of place as I was still wearing the same clothes I had been for the last four days as my luggage had still not arrived from Amsterdam. (It would be waiting for me when I got back to my lodgings later that evening.) I headed up the road to the Meiji Shrine, which was located in the middle of a lush forested park, containing over 100,000 trees donated from all over Japan. This shinto shrine was dedicated to the Emperor Meiji, under whose rule the country started to open up to the outside world and modernise in the late 19th Century. The shrine dates from 1920, but the current building is again a reconstruction, following the destruction of the original during the war.

Bright red torii gates mark the entrance to Shinto shrines, (they were brown in this case) and once inside there are very specific rituals that you need to follow. First you must wash your hands at the purification fountain using the ladle provided, then proceed to the offering hall, made a donation, bow twice, clap your hands twice, pray, then bow again. Sometimes there is a bell, which you can ring once you are finished. These shrines, like the Buddhist temples, are beautifully cultivated, extremely well maintained, and are magnificent bubbles of serenity in a pulsating metropolis. I visited many in the time I was there. Some were world class sites which drew in thousands of tourists, while others were modest neighbourhood shrines known only to locals. But all these places offered a quiet space to stop, stare and reflect. The koi ponds were some of the most attractive features, but the fish, a mixture of orange and white, while wonderful to view, often behaved viciously, as if they were auditioning for a role in the Japanese version of ‘Jaws’. Aside from earthquakes, tsunamis and volcanos, they looked like the most threatening things in this country.

I took a stroll through the huge woods that surrounds the Meiji Shrine, and could as easily have been in the Amazonian rain forest than just a short stroll from the bustling shopping and entertainment district of Shibuya, which was my next stop. Tokyo is very much a city where life happens on the streets, and nowhere is that more evident than at the famous Shibuya crossing. This intersection is busiest pedestrian crossing in the world, with an estimated 3,000 people traversing when it is their turn. One is tempted at this point to ask the perennial philosophical question why all the people (I couldn’t see any chickens) are crossing the road? Many are doing so to take photos and selfies as much as to get to another place. I walked across several times myself, and yes I did take lots of photos, but it actually felt vaguely transcendent to be a part of such a large crowd of people as they merged into one large mass of bodies in the middle of the intersection and then diffused back into individuals on reaching the other side.

If there is ever a global shortage of neon, then Shibuya will be the place to plug the gap. Every time I thought I had reached peak neon in Japan there was a place around the corner that surpassed it. Shibuya would take some beating though. I took a stroll around some of its more prominent streets, like Centre Gai, where Japanese fashions come alive, Supeinzaka, known as Spain Slope for its apparent resemblance to Spanish streets (I stress the word apparent as I didn’t see much), and Love Hotel Hill, where couples can rent rooms by the hour, should they be so inclined. All that sensory overload was enough for one day, and so I decided to go back home. I hadn’t quite figured out how I’d get there, as there weren’t any trains linking Shibuya to my neighbourhood. I took a train to the central Tokyo Station and I knew I’d find a connecting train there.

I have no great interest in trains beyond the practical, and while stations I’ve visited have run from the sublime (New York’s Grand Central) to the ridiculous (Delhi), there’s nowhere in the world quite like a Japanese train station. Tokyo Station is a city in itself. It has malls, food courts, a hotel, and a gallery as well as trains that lead everywhere in the city and the country. Its a labyrinth of planforms and passage ways, with around half a million people passing through every day, and like everything else in Japan it works seamlessly. I found it astonishing that so many people could live in one city, and yet there’s no evidence of crime, antisocial behaviour, or even littering. Were Japanese people happy? They worked very hard, they lived by very strict codes of behaviour, and while there seemed to be a lot of repression simmering under the surface, their society seemed to work and it worked very well. As a visitor I couldn’t say whether the trade offs they made to live in such an efficient society were worth it, but I certainly liked what I saw, and wanted to see a lot more.

GHOST TOWN

Japan suffered a massive property bubble in the 1980s, the same kind that hit much of the west 20 years later. At one point, before the crash came in 1991, the grounds of the Imperial Palace, measuring 1.15 square kilometres, were reported to have been worth more than all the real estate in California. Located in the district of Chiyoda, and surrounded by towering office blocks staffed by white shirted company men, the Imperial Palace may not be worth as much as today as it was in the 1980s, but it’s still unlikely anyone but Warren Buffet could afford to buy even a scrap of it. Surrounded by moats, and protected by high walls, I ventured inside to see the East Gardens. These imperiously cultivated spaces are certainly fit for an emperor, but today they’re free for all to enjoy. Well kept gardens are always a joy to the senses, but there is something that sets the Japanese ones apart. These are conceived in the minds of great artists and executed by the finest crafts people. To set foot in the finest of these places, as the grounds of the Imperial Palace surely are, brings not only peace and joy into our lives, but almost allows us to enter into a different state of consciousness. It feels like being inside a dream.

When planeloads of Japanese tourists first hit the shores of the West in the 1980s we mocked them for their incessant photo taking. Now that I was in their home, I couldn’t help but take hundreds of snaps of their gardens, shrines, streets, buildings, fire hydrants and just about everything else as the whole place was just so new, so inviting, so very photogenic. And I didn’t see any Japanese people mock me either, as that’s just not the kind of thing they would do.

I walked briefly through the shopping district of Ginza as I made my way to my next destination. For those armed with credit cards and materialistic desires, then Ginza is a consumer’s paradise. I was headed for some place that was a marked contrast to the malls and high end boutiques of Ginza, but one that was no less exciting or animated with life: the Tsukiji Fish Market. This cozy warren of narrow lanes, each packed full of eateries and fish shops, is a slice of Japan from a very different era. While much of Asia still does business on the street, it’s now quite out of place in this hyper modern country. Perhaps because of this, the fish market is one of the more popular sights in Tokyo. The variety of seafood for sale here is as delicious as it is diverse. For those who wish to get up early in the morning you can witness the daily tuna auction which takes place nearby. Owing to jet lag I gave the auction a miss, but the street food I sampled in that market was certainly worth getting out of bed for.

Despite being as vast a city as one could imagine, much of Tokyo’s main areas of attraction were in a relatively compact space, relative, that is, for someone who has walked five caminos. Getting from place to place required a daily commute on foot of around 15 kilometres, which would cater for my step count as well as affording me the chance to see the city in all of its glories. My next port of call was the Hama Rikyu gardens, just a short walk from the the Tsukiji Fish Market. Perched on the shores of Tokyo Bay, with the iconic Rainbow Bridge visible in the distance, this majestically composed garden was once a feudal lord’s residence and duck hunting grounds. It’s now a place where you can amble through shady bowers, stroll around a tidal lake, or watch butterflies dance in the flowers, all in the shadows of the busy skyscrapers nearby. It may not have been worth as much as the state of California in the 80s. You could probably have got it for the more affordable price of a New York or a Connecticut.

Stunningly serene as Hama Rikyu was, I now needed my daily fix of neon and high kinetic city life to get me through the rest of the day. So I ventured off to fashionable hopping hotspot called Roppongi Hills. I caught a brief glance of the totemic Tokyo Tower en route. Built in the 1950s in the style of the Eiffel Tower (and 13 metres higher), this structure came to symbolise Japan’s rebirth following the war. Much of the rest of the city has now grown up to match its heights, and no where is this more evident than Roppongi. Another beguiling district of restaurants, bars and nightclubs, this neighbourhood boasts some of the most ambitious new developments in a city that is ever trying to reinvent itself. A modern art museum on one of the top floor of the 238 metre Mori Tower was my main reason for visiting. This, I discovered on arriving, was closed, but there was a temporary exhibition on Manga comics instead, which I decided to explore.

Manga is a series of diverse animated genres, ranging from the historic to the futuristic, concerning itself with everything from daily life to the heroic adventures, and read by people of both sexes and all ages. It is a quintessential feature of Japanese life, and one the country’s primary cultural exports. At the end of the enjoyable and informative exhibition I arrived out on a corridor which offered glorious views of the city at night. Trails of headlights and taillights marked out the streets below, where the city’s millions of inhabitants made their way home from work, or headed out for a night on the town. The windows of offices and apartments glittered like precious jewels, with each one of the countless lights having a hundred stories to tell. This gleaming display of the nighttime metropolis was a multilayered snapshot of a city too big to be fully comprehended or appreciated in all of its detail or complexity. I just stood there and watched this dazzling sight in amazement. Looking out on this vast intriguing city I was struck by the humbling thought that it had no idea I even existed. I was a ghost in this town.

The rain bore down on the city the following day, which I cunningly avoided in the cavernous confines of the Edo museum, dedicated to the history of Tokyo. Later I sought shelter in the Hokusai museum, featuring the works of the great 19th century artist, including his many views of Mount Fuji, and ‘The Wave’, perhaps the most famous of all Japanese paintings, and finally I stood in from the rain in the shopping complex at the base of the giant Tokyo Sky Tree, which I didn’t summit due to heavy mists and high costs. During the day I tried to get tickets to see the Sumo wrestling, which was in season at the time, but it was sold out for the day so I had to watch the contests outside on a television, in the rain. I did see some wrestlers on the street as they walked from their training grounds, known as ‘stables’, to the arena. These certainly were men of considerable size, who looked particularly incongruous in a land where obesity is uncommon, but were they walking down a street in America, or many European cities, they’d probably be regarded as normal.

Those were my final experiences from my rollercoaster visit to the biggest city on earth. The following day I was spirited away from Tokyo by the super smooth Shinkansen bullet train to the forested resort of Hakone, and from there I ventured on to Kyoto, Nara, Osaka, Hiroshima, Fukuoka, Shimabara, Kumomoto, and Nagasaki, before returning to Tokyo, dazed, dazzled, enthralled and exhilarated, three weeks later. I had two more full days in the ultimate metropolis before starting the long journey home. It may not have been a lot, but I hoped to cram a lifetime into those 48 hours.

TOKYO TAKE 2

I began my second adventure by paying a return trip to Ueno Park, where I visited a zoo well stocked with exotic animals, like the jackass penguin and the false tomato frog (they mustn’t have had any real ones), before venturing on to a series of neighbourhoods nearby which are known by the collective name of Yanesen. This is a region of Tokyo that has a distinctive air of old Japan. The traditional streets of this district were home to many modest shrines and temples, coffee shops, tiny art museums and galleries. This was an idyllic place to spend a quiet afternoon in the world’s most expansive city. Yanaka Ginza, a street with a variety of small businesses and an open market selling all kinds of everything was a hive of industry and a bustling place to visit, but when I wandered down the tree lined streets nearby, and in and out of small peaceful temples located on them, I hardly saw another person. One wonders if the locals were preparing for a pandemic, or was this further evidence of Japan’s declining population?

Many of those absent people may have been residents of my next destination: the Yanaka Cemetary. It looked a very serene final resting place, not that that makes much difference to the residents. I could have paused here to consider the meaning of life, death, and all that stuff, but I just wanted an ice cream at that point. There would be time enough for that philosophising when I got home. Green tea ice cream, a Japanese delicacy that can be both healthy and decadent, trumped existentialism at that point. Moving on, the wide variety of small art studios in this region offered a wealth of curious modern art exhibitions. One was owned by an American glue artist called Alan West. I spent a few minutes in this place, looking at his art and reading up on his life. Strangely, I noticed after a few moments, I was the only person in there. There weren’t even any staff. If that studio had been in Ireland all the art would have been looted and put up on Ebay. But not in Japan. If you check your thesaurus for a synonym for honest you’ll find Japanese in the options.

Yanesen’s charms were difficult to tear myself away from, but the clock was ticking, so I hopped on the subway and headed for the Samurai Museum in Shinjuku. The samurais were the warriors of ancient Japan, who made up the ruling military caste during the Edo period (1603-1868). This when the country closed its doors to the outside world, and consequently its own indigenous culture was able to develop unaffected by outside influences. The museum gave an interesting overview of their history, provided a live sword demonstration, and best of all they allowed us to dress up in Samurai uniforms. Those warriors must have been tough men indeed, as the helmet alone weighed the same as a baby calf. I experienced serious neck compression wearing it, and I was only posing for a photo. Imagine if I had to go into battle? Or even bow to my master? I’d imagine the compensation claims by ageing samurai must have been exorbitant.

Shinjuku at night is tinsel town. Walking through its colourful streets is like seeing the world in HD. I did a little window shopping as I sought out a place to eat, settling finally for a tempura restaurant. This dish of battered deep fried vegetables, shrimps and chicken was one of the less healthy options in Japanese cuisine, but no less delicious because of it. It was approaching 7 PM when I finished dinner. I was staying on the other side of town, and planned to take the subway back to my accommodation, where I could then relax for the evening. However, being as it was my second last night in the country, I decided it might be a better option to walk. How many other chances would I ever have to walk across Tokyo on a Friday evening?

Cities at night have an air of intrigue and mystery, sometimes they have an air of menace as well. Tokyo certainly didn’t have the latter, but it had plenty of the former. Its luminous boulevards had stunned me from the moment I had first set foot in them several weeks before. But Tokyo at night was not all bright lights and glittering signs. So much of it was empty and deserted. Though relatively early in the evening, I had most of the city to myself at that early hour. On my epic odyssey across town I was intrigued by the sights of massive empty office blocks where all the workers had gone home, I marvelled at the ornate displays in the windows of closed shops, and the ambient interiors of restaurants where people congregated to enjoy the weekend. I called into a few shrines en route, which remained open but had few visitors after the sun goes down. Tokyo at night is a magical, enchanting place. I could have wandered around here forever, constantly enthralled by its curious blend of the hyper modern and the very traditional. I would be sorry to leave, but I had one more stop before I went home.

The manmade island of Odaiba in Tokyo Bay was a place that had loomed large in my imagination for many years prior to my visit to Japan for reasons that are too complex to mention here. It was originally constructed as a series of forts during the end of the Edo period in the 19th century to protect the city against attacks from outsiders, especially from the gunboat diplomacy of the American Commodore Perry. In the 20th Century these islands were joined together and during the 1980s it was turned into a space age styled residential and business district, just before the property bubble burst and it was left lying idle for the next decade. Today its fortunes have changed. Odaiba is now Tokyo on steroids. It’s packed full of shopping malls, some of whose decor rivals high end art museums, (or how high art museums would be recreated in Las Vegas casinos), ritzy hotels, a miniature of the Statue of Liberty, and the inimitable Fuji TV Building, which looks like how the 21st Century would have been envisioned in the 1960s. Odaiba even has its own beach, though swimming is prohibited. Perhaps its most eye catching feature is the iconic Rainbow Bridge which connects it to the mainland.

I had seen many photos and videos of this place prior to setting foot there, so to actually be there in person was like breaking through the fourth wall. I spent the morning getting lost in Odaiba Decks, a mall which had a floor that recreated a Japanese street from the 1960s. It looked more like the 1980s to me, but Ireland was always a few decades behind the rest of the world. In the rooftop food court I enjoyed a bowl of ramen for lunch and the expansive views it offered of Tokyo Bay in the background. By the afternoon my time and energy levels were starting to run low, so I headed for the Odeo Onsen to recharge my batteries. Onsens, or public baths, are a key feature of Japanese life. I had enjoyed a few during my visit, but this one was the Disneyland of onsens. It wasn’t the cheapest (about 3000 Yen or €24), but for this I got to wear a kimono, which was probably worth the admission price alone. People with tattoos are not admitted, as tattoos in Japan are associated with organised crime, and onsens have very strict codes of conducts and rituals that must be followed. The penalties for violating these were not spelt out, but expecting them to be very severe I did exactly what I was told.

The Onsen was a great way to relax for the afternoon, sweat out the toxins, and become even cleaner than it was possible to be in a land that has no dirt to begin with (apart from the nuclear fallout from Fukushima, but that’s largely invisible). I made my way back through night time Odiaba, passing through more entertainment complexes where the streets were paved with neon. I had taken the train across the Rainbow Bridge to Odaiba that morning, but decided to cross back on foot. It was a warm October evening, and a gentle breeze rolled in from the sea. The bridge was a flurry with traffic whizzing to and fro, trains rolling overhead, and pleasure boats cruising on the water beneath. The skyline of Odaiba glittered and glowed in all of its night time luminescence as I took one last look at it from the bridge. A massive ferris wheel rotated in a spectrum of dazzling colours in the distance. It was an unforgettable sight, a fitting final image of my epic odyssey to the East. But now it was time to go home.

I departed the country from Narita airport the following day. Reflecting on my four weeks in this country I was struck by the fact that even in my forties it was still possible for me to be fascinated, exited and beguiled with life in a way I thought I no longer could in middle age. I had only scratched the surface of Japan in my month long stay, but what I’d discovered was a land where tradition can peacefully coexist with high tech, where public services and utilities work with wonderful ruthless efficiency, and where millions of people can live peacefully together with a very strong sense of duty towards the collective good. A longer stint in the country would obviously give more opportunity for the novelty to wear off and see the cracks that lie beneath the surface, but as the plane departed and I headed for home I was grateful to Japan for one thing more than most: to be filled with a sense of wonder again.