LAYOVER BLUES

Layovers can be the perpetual curse of travellers. No one wants to be stuck inside an airport for hours, where they have to contend with hoards of anxious tourists, massively overpriced restaurants, and a shortage of seats which, if you’re lucky to snag one, will probably facilitate back problems later in life. Should you need to take a nap under such circumstances a general anaesthetic would come in handy, but if you had packed the right materials they were probably confiscated at security before you had a chance to use them. GSOH is always an attractive characteristic in a dating profile, and along with the patience of a saint it is often a necessary quality for surviving anything more than a three hour gap between flights.

Airports are not designed as places where you can switch off easily. Loud announcements blare over the PA, while LED lights and neon advertisements pound your brain with the electromagnetic equivalent of arsenic. They are places where you kill time by reading, scrolling aimlessly on your phone, or browsing purposelessly in expensive shops which try every trick under the sun to get you to part with your last few bits of the local currency. That said, I love airports. They pulsate with energy and radiate with the excitement of people jetting off to places near and far. I get a rush from seeing large hulking aircraft taking off and landing, and when I have time to spare I like to wander past the gates and see people boarding planes for exotic locations like Hong Kong, Honolulu or Hyderabad. Airports are the nexus of the world. If you have time that needs to be put out of its misery, there are far worse places than airports to kill it.

CHINA CAN WAIT

Some airports like Heathrow, Schipol or Charles de Gaule are so vast they resemble cities. A few aspire to be spaceports from the 22nd century, like the unmissable Hamad Airport in Qatar, while others, like Tribhuvan in Kathmandu, have a 19th century feel, as though the goats need to be cleared from the runway so the planes can land. And then there are some that are routine and functional, perfectly suited to getting on and off a plane, but not offering a lot else in the way of diversion or amusement if you have to wait for another flight. Xiamen airport is a prime example of such a place. Located on China’s southeast coast, not too far from the island of Taiwan, Xiamen is a prosperous metropolis of 3.5 million people, and it has a reputation for being one of the country’s most liveable and romantic leisure cities. Like most people from the West, I had never even heard of the place prior to having a three hour layover there before catching a connecting flight to Japan.

I landed in the early morning while it was still dark. It was my first time in the world’s most populous nation. I had to navigate the usual litany of challenges that face every passenger landing in a foreign airport; immigration (particularly exacting in China), check in, and then the arduous process of emigration. By the time all that was done it was time for me to board my next flight. A guy I’d met on the plane asked me if I would now claim China as one of the countries I had visited on my travels? I could see distant roads, apartment blocks and office buildings through the windows of the airport, but I felt I couldn’t honestly say I had really been in the country without standing on the Great Wall, visiting the Forbidden City, or at least walking down a regular street. No. I couldn’t tick China off the bucket list yet. Visiting an airport isn’t the same as visiting a country. It probably is if you break the law, but I wasn’t planning to test that hypothesis.

THE FORBIDDEN CITY

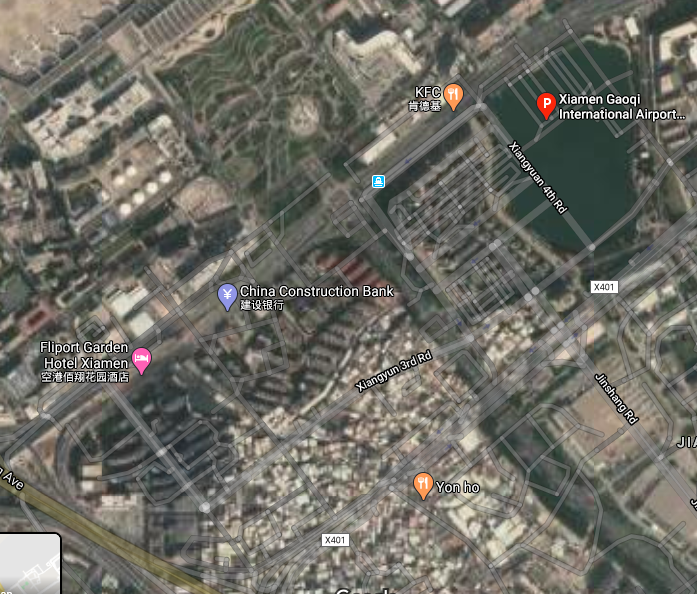

Following an unforgettable month in Japan, I had to navigate the obstacle course of Xiamen Airport again on my return home. As I stood in line at immigration a stern looking officer scrutinised my passport, then stared at me with suspicion. He called over his colleague, who looked me up and down as if I was a fugitive war criminal or an enemy of the ruling communist party. After a few minutes of this charade they stamped my passport with a temporary landing visa and waved me through. I had three hours to kill before check in opened for my homeward bound flight, so I wandered up and down the compact airport terminal for a while trying to find something to distract me. I had no Chinese currency, so I couldn’t spend any money in the top brand stores or western fast food chains (no traces of communism here). I wasn’t really too interested in reading whatever books I’d brought, and I couldn’t access much of the web as it was off limits behind great virtual firewall of China. I reached the entrance to the terminal where some taxis and cars were stopping to drop off passengers. As there was no security I decided to go outside for a look.

For a lot my life I’ve been apprehensive when taking risks. As a surviving catastrophiser I’ve always asked myself, “What’s the worst that could happen?” when I was about to step into the great unknown. Usually, I was able to compile a list with at least 147 items on it, each of which tempered my taste for risk. However, my fears, inhibitions and neuroses have tended to decline with age, and my desire for adventure has increased. Now, I was about to venture out from an airport in one of the world’s biggest police states into a city where I had no idea what lay around the next corner. Google maps didn’t work, I didn’t speak a word of the language, and as a tall white guy I stood out like a sore thumb. What’s the worst that could happen? If anything went wrong, I would probably have been shipped to a labour camp and never be heard of again. That’s what. Taking all that into consideration I decided to go out for a walk.

The grounds of Xiamen Airport are fronted by a curious landscaped maze, with some interesting metallic statues on display. I wandered around this area for a while, and then headed for the main road a few hundred metres away. It was 7pm on a Sunday evening. It was hot and humid. A few cars drove up and down, and a few locals waited at a pedestrian crossing, but otherwise things were quiet. I turned right and walked in the direction of a foot bridge over the main road. I passed by a large office block which was closed, but in a space outside there was a group of people dancing in the open air. They seemed to be having a wonderful time. This wasn’t what I expected to see in a totalitarian state.

My curiosity drove me to go further. I was outside the airport but I still didn’t feel I was properly in China. I could see some lights at the other side of the foot bridge, which looked like a shop front or some business. I ploughed on, passing a series of young couples enjoying the evening air as I crossed the bridge. Although I had to remain very focused on the time and the path that I was taking, I was very excited to know what was up ahead. When I got to the other side and turned the corner I was confronted by a blaze of neon that ran up and down both sides of a street crowded with people, tiny shops and traders. Now I was most definitely in China.

CHINATOWN

The secret to inner peace is to immerse yourself so completely in the present moment you have no opportunity to let unnecessary thoughts disturb your focus. As I wandered up this street I achieved one of the highest states of Zen I had ever reached in my life. The narrow street twisted and turned, and people hustled and bustled in all directions. A few motorbikes and the occasional car tried to progress slowly through the thicket of pedestrians. The streets were lined with small restaurants and shops selling clothes, groceries and mobile phones. Outside, vendors sold food, ranging in variety from roast potatoes to chickens’ feet. The locals chatted, laughed, and argued. Some spat on the ground. Most people were well dressed and looked relatively prosperous, but the neighbourhood still had the air of something from the latter decades of the last century. This was China at its purest.

Each step I took was a step into the greater unknown. My cortisol levels were skyrocketing, my survival instincts heightened, and my senses were at their sharpest. Every noise, object and colour registered with me more clearly than it would on an ordinary street. Everything was new, novel and intriguing. It also had an air of danger. Nobody posed a threat to me. Surprisingly, no one even paid the slightest attention to a tall European man wandering through a district that was rarely frequented by tall white people. I was taken aback at one stage when I saw someone that looked like my father at the rear of a shop, but then I realised it was just my reflection in a mirror. Despite the intense presence I enjoyed, at the back of my mind there was the worry that something could go wrong; I could get lost, or have an accident, or drop my passport, or worse. That’s when the trouble would really arise, because ultimately I was not really supposed to be where I was.

Everywhere I looked I saw small little businesses that buzzed with activity. Customers hurried in and out of curiosity shops, and I too itched to go in and have a rummage around, but I didn’t have any local currency. I wanted to sample some of the fascinating food on sale from street vendors, though maybe I’d give the chickens’ feet a miss. Each laneway I passed, many of which were no wider than two people, beckoned me to investigate, but time wasn’t on my side. If I didn’t return to the airport by 9 my carriage would turn into a pumpkin, and my stay might be extended indefinitely, but in far less exciting surroundings. Like a fussy football manager I assiduously eyed the clock, and on reaching a junction I decided now would be a prudent time to head back to the airport. But rather than retrace my steps I decided to have one more adventure and take a different route back.

My spiking cortisol went up a few more notches as I ventured right off the already beaten track. I had no map, GPS or street signs to follow, only my innate sense of direction, which I trusted implicitly as it had once enabled me to successfully navigate the insanity of Old Delhi. I now found myself in a quieter, more residential area of Xiamen. As I walked through I could see into people’s kitchens and dining rooms, where they ate bowls of rice with chopsticks and watched black and white portable TV sets similar to those that were all the rage in Europe in the 1980s. Living standards may have skyrocketed in China in the last 40 years, but these scenes illustrated that many people still have a way to go before reaching contemporary Western levels. How this country will negotiate the desire for more things with a world that is struggling to manage the fallout from increased consumption will be one of the biggest existential challenges facing humanity this century. However, at that point my most pressing existential concern was getting back to the airport.

While I technically didn’t know where I was, other than being in China, I wasn’t actually lost. I navigated the warren of tiny little lanes, judging where and when I should turn and hoping that if I calculated correctly I would find myself roughly back where I started. Fortunately, my sense of direction served me well, and I soon emerged onto the busy street where I had entered this neighbourhood. I returned to the bridge I had crossed and followed the road back to the airport without encountering any problems or difficulties, passing the group of street dancers en route. Had the Chinese state police been monitoring me all the while? Were there CCTV cameras tracking my every move? Possibly, but I doubt it. This country may be a repressive dictatorship, but I’m sure it has better things to worry about than an Irish guy going for a wander while killing time between flights.

I was just outside the airport for one hour, but in that time I had experienced as much excitement and adventure as a normal holiday would provide. And much of the fun came from the fact that it was so unexpected, so rich, so authentic, but also just a little bit illicit. I subsequently discovered that the neighbourhood I had explored was called Andou, but there was scarcely a mention of it on Google, which goes to show that China’s firewall does a very good job not just of keeping information out of the country, but also inside it. I may never get a chance to visit Beijing, Shanghai, or witness the majesty of the Great Wall or the Terracotta Warriors, but that short trip through an unknown neighbourhood gave me a taste of China I would never forget.

So, next time you have a lengthy layover don’t think of it as time to kill. If you do get a chance, go outside the airport and explore, even if you don’t know what lies around the next corner. Do it especially when you don’t know. Yes, the worst could happen, but what will probably occur will be far more memorable than splurging in the duty free or reading a few chapters of that novel you bought to drown out the drudgery of the airport experience. You may stumble upon a microcosm of the host country, and enjoy a mini holiday for less than the cost of an overpriced airport burger. Be daring.